Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) move students' thought processes beyond just memorising information. How can you go about building these skills into your everyday teaching and what are some of the simple activities you can use in the classroom?

These questions were explored in a recent sharing session with 100 primary educators in Bandung, hosted by the Indonesia office of the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) in collaboration with GagasCeria school. Presenter Stewart Monckton – a Research Fellow at ACER – says the simple message is that if we teach children to think, rather than just remember, all of their academic performance will improve.

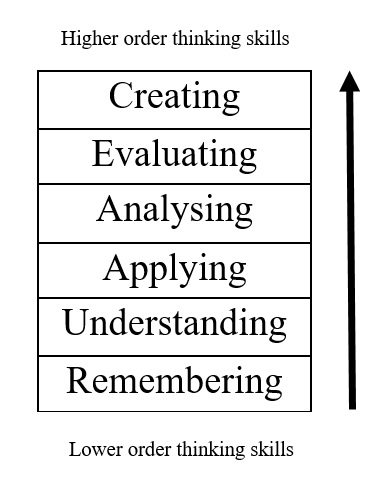

‘Facts are still important, but these days we have different ways of getting them. A smartphone can bring facts to me at the speed of the internet connection. Facts are easier to get hold of – we should think about what we do with the facts, and this is HOTS. It's about moving beyond remembering to understanding, using, making things which are new, solving problems.'

What are Higher Order Thinking Skills?

Bloom's taxonomy revised. (From Anderson, L. W. & Krathwohl, D.R., et al (2001).

‘All around the world, teachers have started to use this approach to thinking skills,' Monckton says. ‘Students can be at different points. It's important to remember these skills are not age related. It is not simply that the low level skills are for young children and the higher order ones are for older children – this is not how it works.'

He told the sharing session there are three areas where these skills really start to happen in the classroom:

- Transfer – remembering, understanding and being able to use what you're learning in a new situation;

- Critical thinking – exercising judgement or producing a reasoned critique of an argument; and,

- Problem solving – finding a solution to an (unfamiliar) problem that cannot be solved using memorised faces or procedures

Where to start

Monckton, who has 20 years' experience as a teacher across the year levels, says these skills are not something extra that needs to be done, they've been in our curriculum all along and this should be the starting point for teachers. To illustrate the point, he shared several examples of statements from the Australian Curriculum that use terminology such as ‘consider', ‘assess', ‘evaluate' and ‘construct'.

‘Go looking to the existing curriculum and find out where they already hide and reveal them. Chances are, it will just be a small change in the way you have to teach. It's not something enormous to start with.

‘My advice is to keep it at the forefront of your thinking when you're planning your lessons, talking to your students, and talking to your colleagues. And when you're thinking about classroom activities, don't even think about trying to include every single aspect of HOTS in one activity – it's too much and it won't work. Think about picking one.'

He says it's important for teachers to separate the difficulty caused by the question from the difficulty caused by the thinking. ‘They need to be difficult thinking questions, not difficult questions structurally.'

For example: student ability may make a question difficult or easy; as may the length of answer expected (a one word answer or an essay); and asking a student to correctly name a number between one and 1000, for example, is difficult, but it has nothing to do with HOTS – although, asking students to devise a strategy to identify the number in the least number of questions might be.

‘Setting our children problem-solving tasks where we don't know what the solution is, that's a higher order thinking skill. Complicated questions are important, but you need to get the level of complication correct – it needs to be complicated enough to allow different children to do different things that answer the question, in different ways.

‘If you're doing a thinking skills exercise in your classroom and everyone thinks the same thing, it's probably not working. If you have a thinking skills exercise in your classroom, different people need to think different things. The HOTS activity also needs to be open enough to allow for low level thinking and high level thinking, and for students of different abilities.'

Simple classroom activities

Monckton illustrated how two simple activities using the same set of common resources found in any school can help you to build HOTS into your classroom practice.

Take three (or more) balls – think about selecting different sizes, colours, patterns, materials and shapes.

- Ask children to sort them into two different groups, and to explain their thinking. This is an activity that can be accessed by all abilities where there is no right or wrong set of answers. Students will come up with lots of different answers and the same groupings will throw up different reasons and discussions. To encourage people to think about the thinking of others, you can ask students to identify the process that others have used to sort.

- Using the same resources, choose a surface to drop them onto. Drop them from different heights. Get the students to discuss and predict what's happening with each ball and why. What will happen if you switch the surface (to grass, for example)? What will happen if you roll them along the floor instead of dropping them, or roll them down a sloping surface?

‘With simple resources, you can immediately get your young children to start collecting information. Ball type one and ball type two. You drop them from the same height. Why does that one bounce higher? The key idea is not that they get the answer correct – the key idea is that they think about possible reasons why.

‘When the students have an explanation for one context, change the context (a different floor, for example). Does the explanation still make sense? What new thinking is needed? What “old” thinking can be retained? It's about thinking about the answer, rather than giving children the correct answer. If, at some points in your curriculum, there are sections about energy and energy transfer, then you can start to think about that, but you don't have to.'

Monckton says not everything you ask children to do has to be higher order thinking. ‘Scaffold the activity with some lower order thinking skills to start with, to help children unpack the task or the data and get them to think about it in simple ways, before you start asking them to think about it in a more complicated way.'

The sharing session focused mainly on science-based examples, but he adds there are lots of simple activities you can use across all subject areas.

Taking small steps

‘Higher Order Thinking Skills really are just a way of improving everyday teaching. My key takeaway message is to think about how we can just slowly, and surely build these skills into your classroom,' Monckton told the sharing session.

‘It's not something that has to occur all in one go, by tomorrow. It's an important step, but it can be achieved in small steps – teachers are flexible, intelligent and resourceful, a good question posed in the middle of the lesson can create more HOTS than you would imagine.'

References

Anderson, L., Krathwohl, D., Airasian, P., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., ... & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Addison Wesley Longman: New York.

Choose a section of the curriculum you’re currently working with. Make a list of the curriculum statements that mention higher order thinking skills.

Now, think about a lesson or topic unit you’re due to teach and choose one of the skills to focus on. Work with a colleague to plan a simple activity to introduce the skill into your classroom practice.